School Consolidation: PR Without Solutions

2016/04/08 – Legislators are using self-inflicted revenue shortfalls to push for major consolidation of state schools, despite consolidation’s limited national success.

House Education Committee members voted to consolidate the municipal district of Winona into its neighboring Carroll County and Montgomery County districts last month. While legislators have since narrowed that consolidation effort down to Montgomery County Schools and the Winona District, committee chairman Rep. John Moore, R-Brandon, said he and his cohorts are already hammering away at larger consolidation efforts in upcoming years.

“I think you’re not going to see 82 (school districts) but something around 50 or less school districts,” Moore told the Jackson Free Press. “All of these consolidations are being done (now) for low performance or an inability to operate financially.”

Mississippi Association of Educators Director Frank Yates pointed out that Moore failed to detail the small amount of savings gathered from the consolidation venture.

“When it came to the financial savings, all they had to offer were generalities,” Yates said. “All they can say is ‘you save money on administration cuts,’ but it remains to be seen how much savings that really is. Let’s say you put Winona and Kilmichael (schools) together. Well, you might save what you’re paying out for one superintendent’s salary and one or two secretaries. But the schools are still going to be there and they’re going to be open, so some form of oversight is still going to be necessary. So are you going to add an assistant superintendent? Well, he’ll make $20,000 less than the superintendent, so when you boil it down, you can’t say you’re going to save a ton of money.”

Yates added that Moore also neglected to point out in his debate that many of the districts are failing financially due to K-12 opponents in the legislature who have voted to underfund state schools by more than $1.3 billion over the last two decades in order to finance multiple corporate tax giveaways. The state cut general funding per student for K-12 schools by 9 percent and funding per student for higher education by 23 percent since 2008. Most notable is the legislative handout of $1.3 billion to the state’s Nissan plant in Canton — the estimated total deficit those same politicians imposed on state schools.

In addition to obvious corporate giveaways, Mississippi legislators also gave corporations more than $300 million in tax breaks and tax credits during the last four years. Last year legislators altered tax calculations for businesses, saving them about $100 million by providing sales tax breaks for developers to build suburban strip malls and sales tax holidays for items such as hunting equipment. Legislators also handed out a reduction in the tax on a business’s inventory, robbing the state general fund of $126 million.

More tax cuts appeared during this year’s legislative session and, though there was already a $65 million revenue shortfall, Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves offered an additional $577 million tax cut proposal. His critics compare that to “fixing” stratospheric credit card debt by quitting your second job.

While legislators struggle to finance tax cuts for their corporate friends by cutting services and reducing schools, public education advocates are arguing that consolidation efforts in other states are having a negative impact on impoverished and minority students.

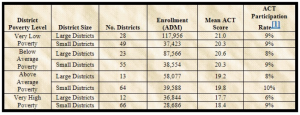

Source: http://www.wpaag.org/Rural%20Trust%20-%20ACT%20and%20School%20Size.htm

The Rural School Community Trust (RSCT) of Arkansas discovered that while students in more affluent districts tend to do better in larger districts, students in poorer communities produce better test scores while attending smaller districts.

“The achievement gap between students from the wealthiest and the poorest communities is much greater among those who attend large districts (ACT score 21.0 for the wealthy, 17.7 for the poor) than among those who attend small districts (20.3 for the wealthy, 18.4 for the poor),” RSCT reported.

The study also revealed that poor students in smaller districts tended to deliver more test scores, in general.

“…[T]he small districts are testing more kids than the large (districts), especially at the poorest income level. At each income level, the student participation rate on the ACT test was either as high or higher in small districts as in large districts,” stated RSCT. “For small districts the participation rate was either 9 or 10 percent for communities at every income level. Small districts with above-average poverty had the highest rate of participation at 10 percent. By contrast, the participation rate in large districts fell as the level of poverty increased. In the poorest communities, large districts got only 6 percent of their students into the test room.”

A Penn State College of Education study concluded that the benefits of consolidating rural schools were limited.

“An extensive account of West Virginia students and their families depicts the experience as inflicting considerable harm,” the study reported. “After the school consolidation (closures), students attended larger schools where they received less individual attention, endured longer bus rides to and from school (and hence longer days), and had fewer opportunities to participate in co-curricular and extracurricular activities (a result of both increased competition for limited spots and transportation issues).”

The university added that students’ families experienced fewer opportunities to participate in formal school governance roles through associations like the Parent Teacher Association and other methods. It noted that increased travel times “proved a barrier to volunteering, visiting classrooms, and taking part in parent-teacher conferences.”

Critics express considerable concern at the possibly of consolidation leading to school congestion. Author Kathleen Cotton observed that stuffing students into bigger schools further alienated students who are already struggling with their studies.

“We know that the states with the largest schools and school districts have the worst achievement, affective, and social outcomes. We also know that the students who stand to benefit most from small schools are economically disadvantaged and minority students,” Cotton wrote, adding that the nation may be acting against the interest of minorities by funneling high proportions of minority youngsters into large schools within very large school districts.

The National Education Policy Center made the same argument in an extensive 2011 report, explaining that “impoverished places, in particular, often benefit from smaller schools and districts, with more teacher interaction, and can suffer irreversible damage if consolidation occurs.”

Like Yates, the report dismissed many state-level consolidation proposals as merely serving “a public relations purpose in times of fiscal crisis, rather than substantive fiscal or educational purposes.”