Neighbors Breathe a Bit Easier

August 17, 2016 – More than a year ago, the Mississippi Sierra Club, the MSNAACP, and coastal activists managed to convince a powerful and obstinate electric company to convert one of the most dangerous coal-burning plants in the country to natural gas.

Mississippi Power built the Jack Watson coal-burning plant near Gulfport in 1957. Since that time it has been the second heaviest emitter of dangerous sulfur dioxide in the nation. Neighbors, many of whom were black or minority, wanted the plant closed, converted, or cleaned. Kathy Egland, an NAACP environmental advocate and Gulf Coast resident, helped organize many of the louder community voices against the plant.

“We had residents complaining of a high use of allergy medicine or greasy airborne deposits on their cars. If this residue was sticking to cars, just imagine what it was doing to your lungs. But we couldn’t get anywhere with Mississippi Power. They were rich, powerful and didn’t care.” Kathy Egland, Gulfport NAACP member and chair of the National Board Environmental and Climate Justice Committee, stands in front of a power plant she fought to convert from coal.

Kathy Egland, Gulfport NAACP member and chair of the National Board Environmental and Climate Justice Committee, stands in front of a power plant she fought to convert from coal.

Fortunes changed over the last five years, however, as the company fell under the black cloud of another one of its projects: an expensive new lignite-burning project set for Kemper County that soon proved to be an albatross around Mississippi Power’s financial neck.

“I didn’t know it at the time, but that Kemper deal was gonna kick their butts all up and down the state of Mississippi,” said Mississippi Sierra Club Director Louie Miller, who also advocated heavily against Jack Watson. “That boondoggle put them in a hole they might never get out of, and made them vulnerable and desperate enough to come around on Jack Watson.”

In 2010, the two Republican members of the three-member Public Service Commission successfully outvoted the lone Democrat on the commission, and they approved a new $2.88 billion price tag for Mississippi Power’s proposed Kemper plant project. Ratepayers would ultimately foot the multi-billion-dollar bill.

The PSC’s eagerness to concede to this exorbitant price tag may have had something to do with direct influence they received from then Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour, who desperately wanted the Kemper plant to happen, as evidenced in the letter he sent to the commission at the height of its deliberations. Barbour’s influence also seems to be more than political, as one of the lobbyists for Mississippi Power’s parent company, Southern Company, was Washington firm Barbour, Griffith & Rogers — notably, one of the firm’s founding partners was Haley Barbour.

Gov. Haley Barbour sent this letter to PSC members, urging them to support a project favoring a company that his lobbying firm represented.

The Mississippi Sierra Club filed a lawsuit in Harrison County Chancery Court immediately after the PSC vote, calling the commission’s decision to approve the price tag “arbitrary” and “capricious.” Soon after, project delays and costs began to spiral out of control. Project setbacks compounded the cost, as they put at risk the millions of dollars in federal tax credits the company first used to help sell the idea of building the plant.

The ever-shifting price tag kept rising repeatedly to thump rate-payers, eventually arriving at its most recent projection of $6.6 billion. Each of Mississippi Power’s 186,000 customers is now conceivably on the hook for $35,000 to pay for the plant, since the company’s sole source of revenue is energy payments from its rate-payers.

The sheer cost of the plant also triggered an investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission and prompted Moody’s Investor Service to downgrade the company’s credit.

Facing trouble at every turn, Mississippi Power decided to settle its litigation with the Sierra Club in 2014, agreeing to convert to natural gas the remaining two coal-burning units at Jack Watson and an additional facility at Plant Greene County in Alabama. They also agreed to retire several other units in Mississippi and Alabama.

Egland praised the conversion, but acknowledged that it probably would not have happened without the tough new federal emissions standards imposed by President Barack Obama and the Kemper-related lawsuit.

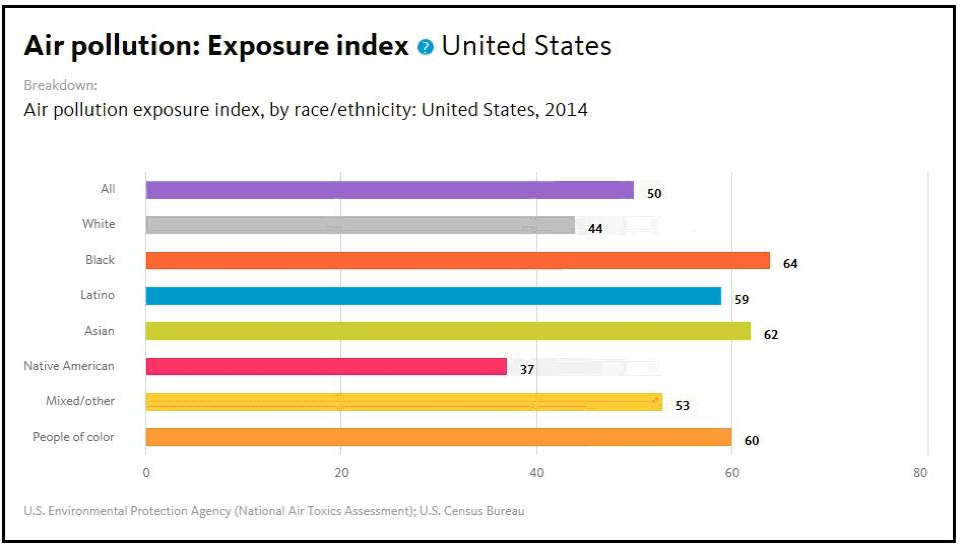

The conversion marks a reversal in a national trend of mixing poor and minority neighborhoods with pollution. Even though African Americans are responsible for 20 percent fewer greenhouse gas emissions than whites per capita, 71 percent of them live in counties that violate federal air pollution standards, according to the Black Leadership Forum. Another 78 percent of the population lives within 30 miles of a coal-fired plant.

African Americans are also almost three times more likely than whites to die or be hospitalized from respiratory diseases like asthma, possibly connected to air pollution, according to the Environmental Justice and Climate Change Initiative. It’s one of the reasons the National Equity Atlas concludes that neighborhoods with high concentrations of low-income families and people of color are more likely “to be exposed to environmental hazards, putting them at higher risk for chronic diseases and premature death.”

http://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Air_pollution%3A_Exposure_index/By_race~ethnicity%3A35886/United_States/false/Risk_type%3ACancer_and_non-cancer

http://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Air_pollution%3A_Exposure_index/By_race~ethnicity%3A35886/United_States/false/Risk_type%3ACancer_and_non-cancer

Black clouds of coal smoke no longer billow out of the converted Jack Watson plant, and Egland said she and neighbors can feel the difference in the air.

“There are people I know in the area who now have drawers filled with allergy medicines, bottles, and inhalers that they haven’t gotten a chance to use because the main culprit is no longer there,” Egland said. “The people don’t win as much as they should, so when it happens, we sure notice.”